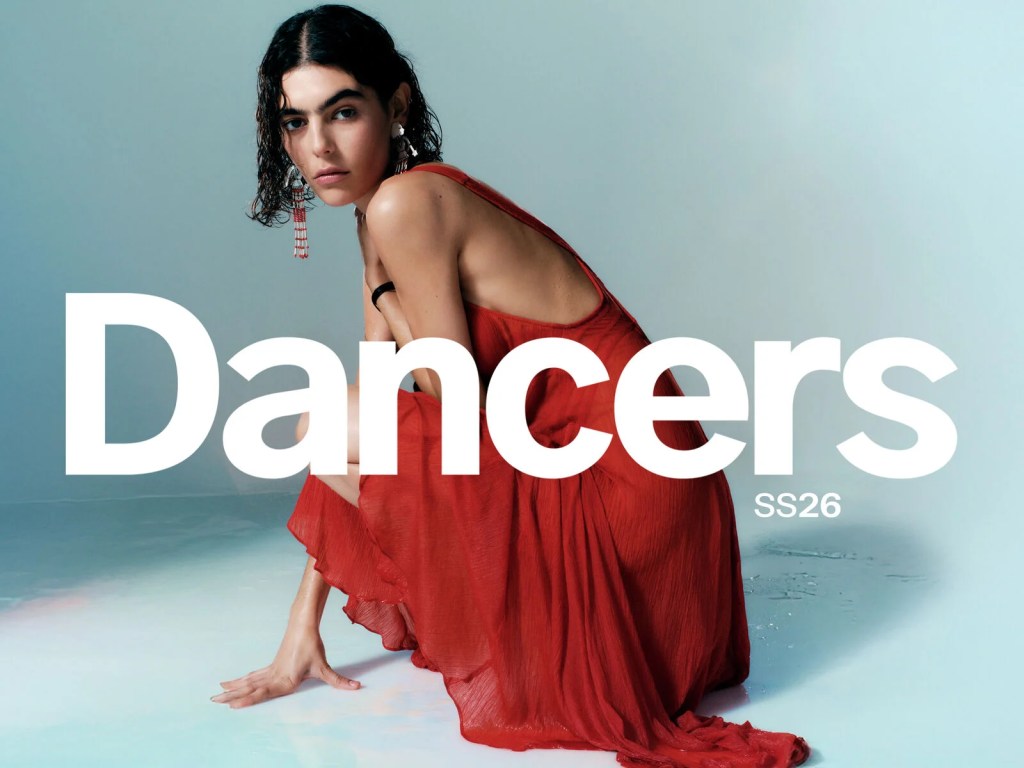

Dancers: From my morning Instagram scroll to the two Bimba y Lola pieces that made me stop, where ballet, discipline and gesture meet in a way that demands attention.

This morning, I was doing my usual, distracted Instagram scroll when an ad from the Spanish brand, Bimba Y Lola, caught my eye with the title of the collection: Dancers. As someone passionate about ballet — a constant practice, almost an addiction — I had to take a closer look.

I’ve never been particularly fond of Bimba y Lola — mostly because of the logos plastered everywhere. Yet I own half a dozen pieces in which both the cut and the materials assert themselves — and, importantly, they are logo-free. They are classic, timeless pieces I wear season after season. In this collection, Dancers, certain pieces immediately stood out for their clear ballet inspiration: precise cuts, carefully chosen materials, and a simplicity that balances functionality with style. I ended up falling for two of them.

It was impossible not to think of the article I wrote for Vogue Portugal in 2023, It’s a Tulle Thing, in which I explored the return of ballet to fashion and the aesthetic referred to as balletcore, which has been evolving over some seasons. At the time, I wrote about how pointe shoe-inspired flats, tulle skirts and romanticised dresses made ballet a visible presence on the streets, translating a bold and unmistakeable form of femininity. But it was never just about romanticising dance: I observed that ballet is not merely apparent elegance; it is repetition, precision, and constant effort that remains invisible to those who watch.

Shoes inspired by pointe shoes, tulle skirts, romanticized dresses, and hairstyles à la ballerina… Ballet has returned to the streets of the world to consummate a shamelessly strong statement of femininity. We want a lighter, softer, more optimistic Fashion. It is therefore time to adopt as much as we can of this graceful trend.

— Pureza Fleming, It’s a Tulle Thing, Vogue Portugal, 2023

Fashion, I argued, captures the gesture and translates it, selecting what suits it, often concealing the training, sweat and discipline that transform the body into an instrument. I also quoted David J. Amado, choreographer and artistic director with experience in international companies, who reminded us that everything in ballet must be beautiful, but the effort required to achieve that beauty must remain invisible.

“We want to see something that takes us to another world, more beautiful, safer, a more absolute world too – because in classical dance, in Swan Lake, for example, the white swan is good, the black swan is bad. It is all very definite and absolute, there is no room for confusion. In our current world, everything is very confusing, nothing is black and white.”

— David J. Amado, choreographer and artistic director with experience in international companies, quoted in Pureza Fleming, It’s a Tulle Thing, Vogue Portugal, 2023

It was this tension — between appearance and discipline, between aesthetic and effort — that fascinated me then and continues to fascinate: fashion does not invent ballet; it merely translates what suits it, hiding the invisible work that creates beauty.

Since then, the language of ballet has spread and diversified noticeably. Lanvin, with Elegance in Motion, explored the intimate relationship between cut and movement, presenting ballet as a real presence, not merely a visual reference. Repetto, with its 2016 fashion film, placed dance at the centre of the narrative, revealing the gesture, discipline and precision that underpin the brand’s aesthetic. Cole Haan drew on dancers from the New York City Ballet to convey functional elegance and natural movement in its campaigns, while Loewe, with the Ballet Runner project, translated ballet gestures into sneaker and technical apparel design. More recently, NikeSKIMS launched a ballet-inspired collection (NikeSKIMS Raises the Barre), bringing this movement language to urban activewear with technical fabrics, study-line-inspired cuts and classic colours.

Observing these collections makes it clear that ballet today is not just a visual trend: it is a language of discipline, control and applied aesthetics. Miu Miu turns satin slippers and micro-cardigans into symbols of disciplined youth; Simone Rocha dramatises restrained gesture with tulle and bows that evoke considered femininity; Alaïa sculpts the body (I’m especially taken with the pink dress featured in Alaïa’s Spring/Summer 2024 campaign); Ferragamo preserves structural memory of gesture; and Repetto reminds us that this grammar began in the studio, not on the Instagram feed.

Ballet returns in unstable times. It is no coincidence. Repetition, hierarchy, and discipline — all structural features of the practice — become a symptom in a society seeking order in chaos. Fashion absorbs this grammar, seeing in it not merely lightness but a set of codes that evoke order and wholeness. The paradox is that, while selling lightness, what truly matters — silence, control of gesture, precision — is the result of intense training and repetition. This duality, between what is seen and the effort that makes it possible, is part of what makes balletcore so compelling: an aesthetic that, on a smooth surface, carries layers of extreme discipline and invisible effort.

And back to Bimba y Lola. To the pieces that assert themselves amid the noise, particularly when the logo vanishes. They remind us that sometimes, all it takes is cut, material and simplicity to capture attention, spark interest, and ultimately make us stop and look — just as we do when watching ballet.

Leave a comment