Why it’s better to have flawed style than none at all.

“A little bad taste is like a dash of paprika. We all need a touch of bad taste. It’s healthy, passionate, physical. I think we could use a bit more. I am, however, against having no taste at all.”

— Diana Vreeland

There’s something almost tragicomic about the way taste has evolved — or rather, dissolved — in the past decades. And perhaps I should have seen it coming:

I first wrote about this tension between taste, imitation, and identity back in December 2017 for Máxima. What felt like an early warning then has now become the cultural wallpaper we all live inside.

Because here’s the truth: having questionable taste is still infinitely better than having no taste at all. At least bad taste has pulse, intention, a hint of the personal. The real crisis is the aesthetic emptiness that now parades as “style,” a sort of algorithm-generated neutrality for fear of getting it wrong.

Having questionable taste is still infinitely better than having no taste at all.

In my time — and I say this without nostalgia, merely realism — we wore things that today would make me shudder.

Coloured streaks dyed at Porfírios in downtown Lisbon.

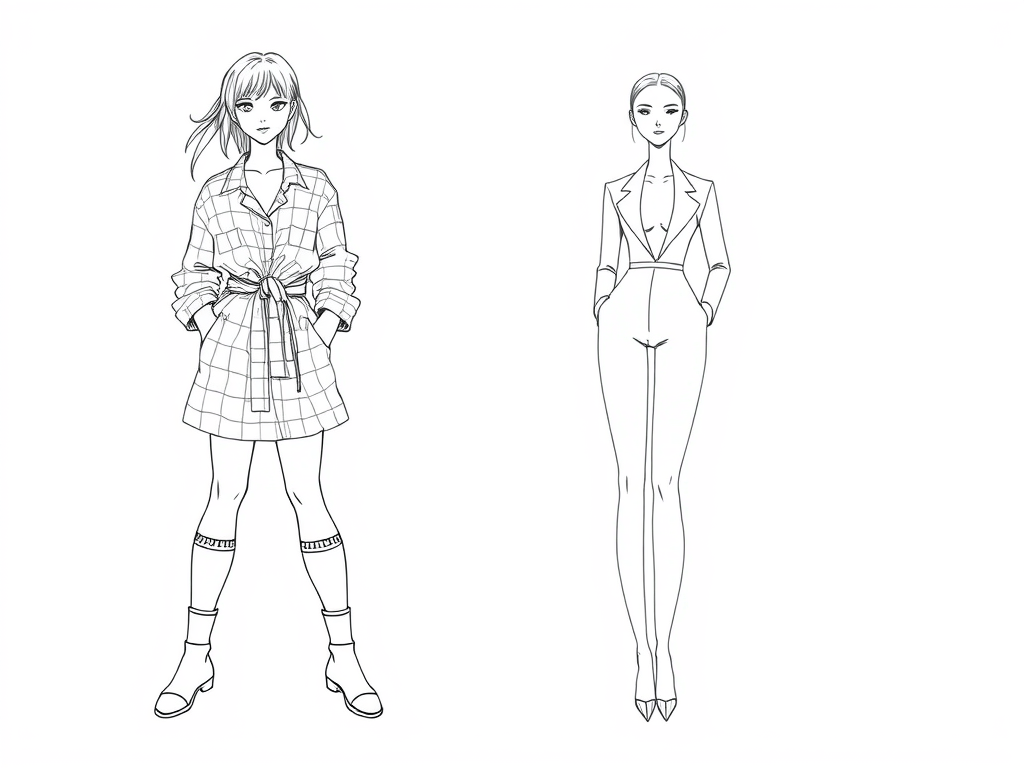

Checked shirts tied around the waist à la Kurt Cobain — mine strategically placed to hide a teenage body that drew unwanted attention.

Over-the-knee socks with kilts and Doc Martens — runway cool, lycée questionable.

Cheap, thin tops with dubious slogans like “handle with care.”

It wasn’t good taste. But it was ours. Intentional, spontaneous, sometimes hideous — yet distinctly authored. It carried context, personality, and risk, even when it failed spectacularly. And in that failure, there was freedom — a playground for experimentation that today’s algorithmic style cannot reproduce.

Today’s Gen Z grew up with infinite choice and no friction. The Internet didn’t just democratise references; it flattened them. Everything is available, therefore nothing is personal. Style became a copy–paste exercise, a collage of Pinterest boards and TikTok “fit checks,” an aesthetic assembled from the leftovers of a global moodboard.

And don’t get me started on the so-called “Portuguese girl style.”

What even is that?

From where I’m standing, it looks like an endless rotation of mismatched pieces pulled from wardrobes bursting with consumption and “options.” Not style — just volume. Not taste — just accumulation dressed up as identity.

I remember, too, the subtle education of error and excess. Every wrong choice was a lesson:

The camouflaged humour of cheap slogan tops.

The absurdity of flannel shirts that doubled as skirts or belts.

The theatricality of over-the-knee socks under a kilt — a look the runway might have adored but which in the school corridor earned sideways glances.

Even the Porfírios dyes themselves, impossible colours, sometimes uneven, always bold — evidence that creativity required daring, not perfection.

We were creative because we had limits. We were inventing in real space, with tactile, imperfect tools, with time and imagination. Today’s landscape, by contrast, is defined by endless virtual options, by immediacy, by reference upon reference upon reference. Limits are gone. And where limits vanish, originality quietly slips out the back door.

We were creative because we had limits. We were inventing in real space, with tactile, imperfect tools, with time and imagination.

So yes, I do not defend the “ugly” of Balenciaga, nor the engineered shock value of modern haute — much of it is simply loud without substance, attention-seeking without risk. But I defend the existence of taste, even when imperfect, because the alternative is worse: aesthetic nihilism, a world of perfectly bland imitation.

We had bad taste, yes. But it was alive, personal, and, above all, creative.

And today, we are poorer for the taste that never even gets the chance to exist.

If you’ve ever felt lost in a sea of copy–paste style, or wondered where originality went, let’s talk about it. Reply, comment, or share your own stories of taste, bad taste, and brave failures. Let’s remind ourselves that even mistakes can teach us how to live — and dress — with intention.

Leave a comment